Calling this article a comparison may seem a little odd since moissanite and diamond gemstones are like apples and oranges in terms of their origin, physical structure and value. However, take a step back from a gemologist’s view of gemstones and look at them through ‘older’ eyes.

Humans have been adorning themselves for over 120,000 years. What have they been decorating themselves with? Back in those pre-historic days, it was whatever looked beautiful and stood out! People would primarily wear shells, feathers and carved bones, and we are not that different today. Jewelry must have beauty and it must stand out, even if we have more sophisticated and precise tastes than back then. Today, beautiful and admirable adornment is available thanks to the incredible world of jewelry! After all, whether in the past or present, people want the best items they can find or afford.

As we know from jewelry, moissanite sparkles like a diamond and is far more affordable. These traits are the focus for comparison. In terms of beauty and sparkle, we’ll observe how moissanite and diamond shape up to someone looking at a piece of jewelry that is both stunning and affordable, while not having the intimidating price tag.

What is moissanite?

All the moissanite you see in jewelry will be synthetic, also referred to as man-made, but it has a fascinating backstory!

Moissanite was produced in a laboratory before it was found in nature. Yes, read that again. Right from the times when alchemists tried to “create” gold many centuries ago, humankind has worked in laboratories trying to copy or improve nature’s creations. In 1891, humanity made a breakthrough when E.G. Acheson created a few dark hexagonal crystals when he attempted to produce diamonds.

This laboratory-grown material was never intended to be a gemstone. Being incredibly hard and wear-resistant, the opaque, black crystals were used as an abrasive material known as silicon carbide and trademarked by E.G. Acheson, as “carborundum”™. It’s interesting to think that carborundum™’s name might have been invented by combining the names of diamond, hardness of 10, and corundum, hardness of 9, for a unique title.

Two years later in 1893, actual silicon carbide crystals were discovered in nature by Henri Moissan. Because Moissan uncovered these natural silicon carbide crystals in an Arizona meteorite crater, this gemstone was named moissanite. Henry Moissan initially believed he had found diamonds until further research was done. Eventually, more examples were found in nature, but they were very rare and it was over fifty years before it was found outside of meteorite strikes.

After this time, examples of naturally formed moissanite were found in environments that suggested a very deep, mantle, origin. This meant that natural moissanite was transported to the surface of the earth by the same geological processes that transport diamonds, kimberlites and lamproites. These examples found in the wild are only suitable for collectors and never in gem-quality crystals.

Fast forward to the late 1990s to a company based in Morrisville, NC, called C3 Incorporated (now Charles and Colvard). This company figured out how to make the near-colorless and transparent moissanite crystals that we see in jewelry today. This was a very exciting product as it was an affordable alternative to diamond.

Moissanite was also a disruptive product and to ensure that the difference could be shown, Charles and Colvard released a tester to help identify their product and distinguish it from diamond. This was to reassure the market that the moissanite was never intended to deceive or mislead, but they acknowledged that over time, jewelry reappearing on the second-hand market would need to be properly verified to protect consumers.

What is diamond?

Diamond is the gem of gems. In its natural form, no other offers the unique backstory, nothing is as old and nothing is as uniquely difficult to cut on account of its hardness. Nothing has had more romance or marketing attached to it and nothing is quite so singularly appealing to the regular consumer.

Diamonds are brought to the surface by a kind of volcanic eruption that starts below the very deepest and oldest parts of continental land masses. Known as cratons, these regions sit under some of the continents like the keel on a boat, and beneath them is an ideal combination of temperature and pressure for diamonds to form, the diamond stability zone. The eruptions, known as kimberlites, that bore diamonds to the surface are millions and even billions of years younger than the diamonds themselves. The youngest kimberlites are around thirty million years old, so diamonds are indeed incredibly rare.

How to tell the difference between moissanite and diamond

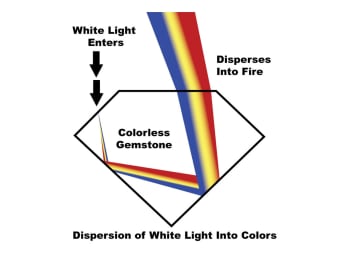

To many in the trade, the first clues are the combination of the stone and the setting together. Because moissanite is a fraction of the cost of an equivalent diamond, it will often be used in affordable jewelry. A trained eye will spot this when the setting is evaluated as gold-coated or mass-produced against a beautiful and high-quality gemstone. In the case of moissanite, it produces an extraordinary degree of spectral ‘fire’ and manages to look very expensive in its own right.

A more technical clue is double refraction, which is a quality that relates to the original crystal form in which the gemstone grew. Diamond is from the cubic crystal system and moissanite is from the hexagonal group. This immediately suggests that a polariscope will tell them apart. It’s also possible to separate moissanite from diamond with a close look through the gem at its facet edges opposite of you. Unlike diamond, moissanite’s back facets will appear to be doubled due to this optical effect.

Moissanite used to be rarely completely colorless and often had a greenish tint to it which would raise suspicion. It took many years for the producers of moissanite to improve the color above about an I or J on the Gemological Institute of America’s (GIA) diamond color scale. Now, seeing E and F is quite common. Moving from moissanite’s color to its clarity, the most likely inclusions early on were occasional acicular needles (needle-shaped inclusions). This is not the case with modern production techniques, leaving most modern moissanite inclusion free.

There is a relatively affordable tester, often referred to as a moissanite tester, available for identifying diamonds from moissanite. This tester allows you to know a material’s electrical conductivity. Moissanite conducts an electric current very well while diamond is an electrical insulator (electrically resistant). Before moissanite appeared on the market, jewelry stores commonly tested for diamonds by measuring thermal conductivity. However, most moissanite will often pass as diamond with a thermal conductivity test.

What is the difference to me?

Moissanite and diamond are tough enough to survive in engagement or wedding rings, which is important to those wishing to have a colorless stone in a traditional ring setting. The gems in an engagement ring need to be robust enough to last decades, and moissanite will manage this better than any other gemstone apart from diamond. Why? Because moissanite has the closest hardness to a diamond. Closer even than ruby and sapphire.

Although both gems are equal in color and clarity, moissanite will show slightly greater fire (dispersion). This means that the sparkle that you see will be more ‘spectral’, and it will show a large spectrum of color flashing at you with reds, blues and greens. It is impossible not to be impressed. In contrast, diamond will show a balance between brilliance, which is the white light sparkle, and fire. With moissanite, the fire will dominate.

An inclusion-free diamond will be extremely costly and most buyers must compromise on what they can live with. Moissanite will almost always be loupe-clean, meaning that looking with a 10x jeweler’s loupe will not reveal any inclusions.

While diamonds from antique pieces are not cut to the finest standard or proportion, moissanite and diamonds in present-day pieces will be well cut. While moissanite is significantly more affordable than natural diamond, it is still costly, and therefore cut with care taken to get proportions and polish right. So, unlike another, much softer, cheaper and less sparkly diamond simulant, CZ (cubic zirconia), the cut is always good.

And finally, a word on the formation of the two gems with some food for thought.

A diamond has made an incredible journey from its formation, possibly billions of years ago, and perhaps over 100 miles below the earth’s surface. It was then transported by a kimberlite, tens of millions of years ago toward the surface where it could be found.

A moissanite that you will find in jewelry, has been man-made in a modern factory.

Since they were both created so differently, perhaps a comparison with laboratory-grown diamonds would be more appropriate.

Laboratory-grown diamonds have been steadily dropping in price, and we can expect them to drop close to the cost of moissanite as production techniques are improved and competition gets fiercer. Prices of moissanite dropped when the patent expired, and other companies brought competition to the market. Would they drop again as laboratory-grown diamonds lower in price? Quite possibly. The manufacturing process for both is expensive, energy-intensive and complicated.

It has been no secret that the resale value of moissanite is negligible, and the same is likely to be the case with laboratory-grown diamonds in years to come.

Conclusion

In summary, moissanite can be a suitable replacement for diamond, depending on what you value most in your gemstone.

Moissanite is hard enough to last a lifetime in daily-wear jewelry, it has greater fire than diamond and whatever size you like will cost a fraction of what a diamond would be. The two can be easily separated through a check for the doubling of back facets and through the use of a moissanite tester.

On its merits (and despite the possibility of a further reduction in the price of laboratory-grown diamonds encroaching on its market space), moissanite will always be around because no other colorless gemstone comes near to that incredible spectral fire. Once it is seen and appreciated, it will always have dedicated fans.

References

Allaby, Michael, Dictionary of Geology and Earth Sciences (Oxford Quick Reference), Fifth edition 2020

Charles & Colvard. (n.d.). Moissanite & Lab Grown Diamond Jewelry: Charles & Colvard Official Store. Moissanite & Lab Grown Diamond Jewelry | Charles & Colvard Official Store. Retrieved from https://charlesandcolvard.com/

Herve Nicolas Lazzarelli, Gemstones Identification - Blue Chart 2019

Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. (2000, October). Mindat.org. mindat.org. Retrieved from https://www.mindat.org/

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, March 10). Edward Goodrich Acheson. Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Goodrich_Acheson

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, March 30). Henri Moissan. Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri_Moissan